Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal

7.0 Historic Development of the Area

7.1 The discovery of Iron Age pottery in an area just off Clarkes Dale is evidence of Great Easton's long history. A Romano-British site in Lounts Crescent and around St Andrew's church developed into the village of Great Easton. Archaeological work (including that undertaken as part of the Time Team television programme in 2003) shows that around 800 AD farmers had started to leave their scattered farmsteads and were living more communally, to form villages. In Great Easton the settlement spread down the hill from the church to the area of the present village, which they called Estone – the east tūn or settlement. This may have referred to its geographical position east of Medbourne (an important early site), or east of Bringhurst, the earliest church. Present-day footpaths pass close to Roman sites, suggesting that these paths may date from Roman times, or possibly even earlier. The name is recorded as Eston in the Domesday Book of 1086, which showed it to be in the possession of Peterborough Abbey. Church ownership continues with several local farmers still renting land from the Church Commissioners. From the sixteenth century, the village is called Easton-juxta-Welland, Easton by Welland, Easton Magna, and finally Great Easton.

7.2 The parish church, dedicated to St Andrew the Apostle, dates mainly from the thirteenth century and is constructed of local ironstone. However, herring-bone masonry in the west wall provides evidence of an earlier building of either Anglo-Saxon or Norman origin on the site. The church only gained a burial ground in 1349 as it was a chapelry of Bringhurst until 1865 when it became a separate parish church. All interments were previously at Bringhurst, but during the Black Death of the 1340s the Bringhurst graveyard began to fill so the Bishop of Lincoln granted a licence to Great Easton to open a graveyard in 1349.

7.3 The Time Team Big Dig of 2003 discovered a significant concentration of Saxo-Norman pottery in the open green space to the south-west of the Village Hall. This revealed that this land was open space containing plot boundaries to the rear of the street frontage and indicates that the village was already well established by the 11th century. The earliest surviving houses in Great Easton are from around 1500. They were built with crucks – pairs of large, curving timbers which reached from near ground level right up to the apex of the roof. Such houses were common in the locality from 1450-1550. Detailed research on village houses in recent decades has found evidence of nine cruck houses, although they often only survive in a fragmentary state. Evidence of these early houses is distributed throughout the village which indicates that the street layout was fully established by the late medieval period. In 1563 there were 70 households in Great Easton.

7.4 From around 1620, rising prosperity and confidence led to a steady transformation of village houses. Often referred to as the 'Great Rebuilding', this saw the whole of the village gradually rebuilt in stone. By 1670 Hearth Tax records show there were 106 households in Great Easton. This seventeenth century period brought the development of a rich tradition of local vernacular architecture. Most houses were built of the local ironstone, but limestone from Weldon was often used for the quoins, windows and doorways. Sometimes, alternating courses of ironstone and limestone were used, giving a striped effect. Chimney stacks were built of fine moulded stone and the most typical feature of the period was the mullioned window. The strong character and quality of craftsmanship, particularly the stonemasonry, of local houses of this period is reflected in the number of nationally listed buildings in Great Easton (see Appendix A).

7.5 Following the building of so many good houses in the seventeenth century, relatively few new houses were constructed in the eighteenth century. However, many alterations took place to existing houses and smaller houses and cottages began to survive. Ironstone remained in general use until the nineteenth century when it was gradually replaced by brick. A local brickyard was established about a mile and half north of the village on the Caldecott Road and the first brick was produced in 1850. Around the same time the Rugby to Stamford railway was opened and this enabled the transportation of Welsh slate to the area for use as an alternative roofing material to thatch or Collyweston slate.

7.6 Although the church of St Andrew was dominant in the village skyline, there were non-conformists in the village from the late seventeenth century. By 1730 two dwelling houses in Great Easton were licensed as meeting-places for non-conformists. In 1798 a new Independent Chapel building was licensed. This was rebuilt in 1830 on the road to Caldecott and the small burial ground of this Congregational Chapel remains today. By 1900 the chapel was no longer in use. It was sold in 1919 and demolished soon afterwards. The stones were incorporated into the garden wall of the former manor house, Greylands, (now 1 Caldecott Road). As early as 1807 houses in the village were licensed as meeting-places for Wesleyans. One of their number opened a Reading Room on Banbury Lane in the first half of the nineteenth century to encourage adults into a more worthwhile activity than the alehouse; of which there were 6 in Great Easton in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1857 a Wesleyan Chapel was built, using Great Easton bricks, adjacent to the village pound in High Street. It was used for worship until the last service took place on 31 August 1986. After its closure it was sold and is now a private house.

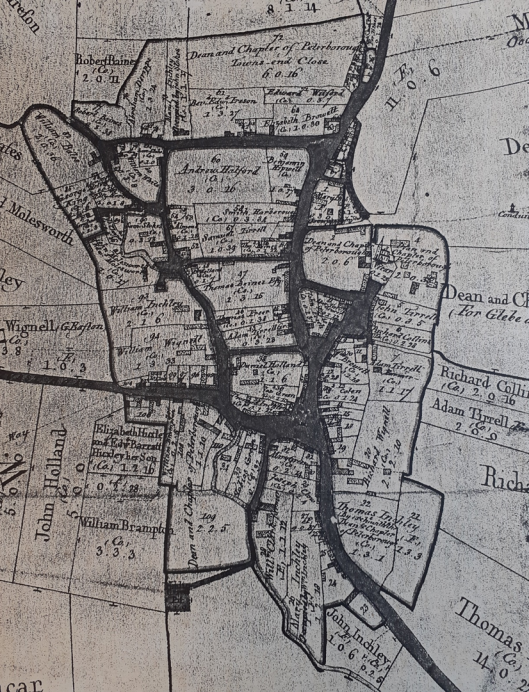

7.7 The enclosure of open and common fields and pastures brought to an end the open strip-field farming system and divided the open fields into the patchwork of fields and hedges we recognise today. The Enclosure Act was enforced between 1806 and 1810 in Great Easton. Evidence of the medieval open field arable farming system used prior to enclosure no longer remains within the conservation area boundary but can still be found just outside the boundary in the ridge and furrow earthworks in fields surrounding the settlement. The Enclosure Map of 1810 gives a very detailed plan of the village at that date, with every house and outbuilding plotted.

Fig.3. 1810 Enclosure Map of Great Easton (Great Easton & District Local History Society Archive)

7.8 The village expanded in the 1800s from 543 inhabitants in 1801 to 600 inhabitants by 1846. Although agriculture was the main source of employment, White's Directory of Leicestershire (1846), shows that there were 4 inns/taverns in the village and residents were employed in a range of occupations. These included 2 blacksmiths, 2 wheelwrights, 2 tailors, a surgeon, a stonemason, 5 shoemakers, 4 bakers, a butcher, 2 shopkeepers, a cooper, a ketchup maker and a stay maker. Mushroom ketchup was made by the Ashby family at Bybrook house from the 1840s to around 1900. Mr Moore, the stay maker listed, founded the Moore and Haddon corset manufacturers. By the 1851 census return a further 14 people were recorded as employed in the production of corsets and by the 1861 census William Haddon is shown as a corset and staymaker employing 1 man, 1 boy and 40 women. Moore and Haddon converted a farm building into a factory on Cross Bank in 1908. This work was undertaken by Mr Brown the wheelwright and carpenter whose workshop was adjacent to his cottage at 6 Caldecott Road. From 1850 generations of the Brown family were the village wheelwrights, carpenters and undertakers for around a hundred years. The firm of Moore and Haddon manufactured corsets in Great Easton for around 120 years until the Corset Factory closed in 1963. It is now a private dwelling. In addition to the former shops, other evidence of commerce in the village can be seen at the 1881 Clock House on Church Bank. The building still retains the clock, set to the left of the building, that advertised this as the home of the village clockmaker. The original workshop still adjoins the house. From here Tom Fox made grandfather clocks and undertook clock repairs and his brother worked as a blacksmith in the forge that was behind the house.

7.9 The twentieth century was a period of change for Great Easton. Between 1909 and 1914 three of the village pubs closed, two of which had operated for over 150 years. Men from Great Easton lost their lives in both World Wars. In October 1920 a cross of Clipsham stone was erected on the village green at Cross Bank as a memorial to the men of the parish who fell in the First World War. Some of the homes these men left behind to go to war carry commemorative plaques which were erected as part of the First World War centenary commemorations in 2014-2018. Other changes to daily life came when most properties were connected to a mains sewerage system in the 1930s, electricity was supplied for domestic use in 1936 and mains water was brought to the village in 1957. The arrival of a regular bus service made it easier to travel to employers such as Symingtons in Market Harborough or to the steelworks in Corby. In 1933 the local lodge of the Ancient Order of Oddfellows purchased a hay wagon shed, on High Street, from the farmer Tom Mould and converted it into a meeting place for the Lodge. In 1954 it was it was leased, and subsequently purchased, from the Oddfellows by the Parish Council and has served as the Village Hall to this day.

7.10 The first new housing of the twentieth century was a row of cottages off Mould's Lane that Mr Mould built for his workers in 1913. This was followed by three pairs of council houses in Stockerston Lane in 1922/3. Following the Second World War four pairs council houses were built in Broadgate and five pairs were built in Lounts Crescent in 1952. In 1931 the population of Great Easton was 349 and this rose to 398 by 1951. Much of the of the development of Great Easton was unplanned until the 1960s when the development of Clarkes Dale and Barnsdale Close took place just outside the conservation area boundary. This was followed in the 1970s by the development of Musk Close off Broadgate.

7.11 The image below (Fig. 4) was taken in the 1960s at the time that Clarkes Dale was in development (bottom left of the image). Not only does it show the setting of Great Easton within the rural landscape it also shows the extent of open space within the conservation area boundary, especially behind Barnsdale and between High Street and Brook Lane.

Fig. 4. Aerial view taken in the 1960s from outside the southern boundary of the conservation area on Barnsdale (Great Easton & District Local History Society Archive).

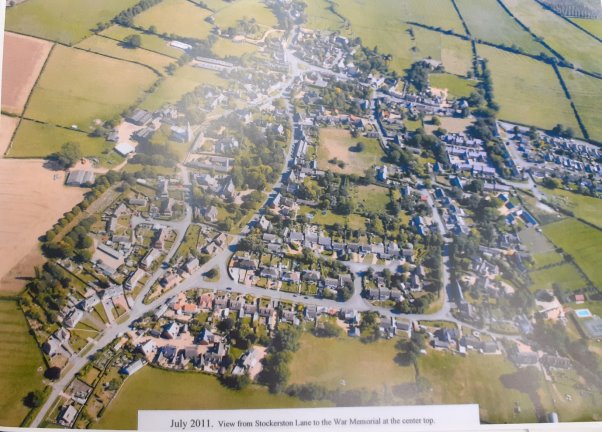

With the new housing developments of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century the population grew from 398 in 1951 to 671 in 2011. The image below (Fig. 5) was taken in 2011 (image is taken from Stockerston Lane - the Clarkes Dale development is now top right of image) and clearly illustrates the increased density of buildings within the village. Although the rural setting in open countryside remains unchanged, the image shows the reduction in green space within the conservation area. Whilst some of the new developments have attempted to use materials to fit with the village vernacular, they have also brought a more suburban feel to parts of the conservation area.

Fig. 5. Aerial view taken in 2011 from the just inside the conservation area boundary on Stockerston Lane. (Great Easton & District Local History Society Archive).