Development Management SPD

10 Landscaping and development

10.1 Local plan policy GD8 amongst others things requires development to be well planned to reflect the landscape or streetscape in which it is situated and include an appropriate landscaping scheme. It is essential to identify and understand the elements that form the existing landscape both in relation to the site itself and its immediate surroundings. Protection of existing landscape features and design of new landscape, whether hard or soft features, are fundamental to the successful integration of a new development with its surroundings and should therefore be designed as part of any proposals.

10.2 For the purposes of this SPD, "landscape" includes all visual features that make up the appearance and composition of the natural environment. From country parks and gardens, to woodlands and meadows, through to street planting and community orchards. All of these make up the landscape that surrounds us and contribute to the distinctive character of our towns and villages.

10.3 The maintenance and enhancement of existing green spaces within the landscape through development is key to the creation of high quality areas which are used and enjoyed by residents and visitors. Quality landscape provision within new developments relies on good design and planning.

10.4 For the purposes of this document, the term "green space" will refer to areas such as parks, gardens, street planting and play spaces etc. All of which make up the wider landscape that surrounds us.

WHY IS LANDSCAPE DESIGN IMPORTANT?

10.5 Well designed, planned and maintained green spaces can be the making of a new development and can have a positive impact on the areas where we live and work. The benefits of well designed green spaces range from increased economic investment through to cultural, social and environmental benefits. Well designed green spaces can also:

- Reduce the predicted effects of a warming climate, particularly in urban areas.

- Improve the health and well being of residents and visitors.

- Reduce crime and provide a "sense of place".

- Significantly increase local biodiversity.

- Increase the value and attractiveness of an area.

10.6 Conversely, green spaces that are poorly planned, have no clear use, and are inappropriately planted and maintained can become underused and run down, often leading to anti social behaviour. Green space which results from the leftovers of development can become a maintenance and financial burden, offering no real benefit to the surrounding area.

LANDSCAPE DESIGN AND PLANNING PROCESS

10.7 Landscape provision and green space design is an integral part of the planning process. Where early consideration is given to landscape matters, new developments tend to have a stronger sense of place and character and a feeling of increased quality.

10.8 When submitting a planning application for development, the Council will expect to see evidence that landscape provision and green space design have been clearly considered as part of the site design.

10.9 The following questions should be used as a prompt when designing a site and also by the Local Authority as a guide to green space design:

1. Does the site sit comfortably within the surrounding landscape?

10.10 All sites form part of the wider landscape and have the potential to impact (positively and negatively) on their surroundings. For all developments, an assessment of the surrounding landscape character should be made and the site layout designed in such a way to ensure that it complements its surroundings. In addition, the potential for the site to "link" into the surrounding landscape should be explored.

10.11 For larger scale developments, the district wide and settlement based landscape character assessments should be consulted to ensure that the intended use of the site does not detrimentally impact on the surrounding landscape.

10.12 These assessments included an identification of Landscape Character Areas and a detailed analysis of the sensitivity of land around the edge of settlements and capacity to accommodate future development principally in landscape terms:

- District wide Landscape Character Assessment (September 2007)

- Market Harborough Strategic Development Area Landscape and Visual Assessment (June 2012)

- Leicester PUA Landscape Character Assessment and Landscape Capacity Study (September 2009) and Scraptoft Addendum (2016)

- Lutterworth and Broughton Astley Landscape Character Assessment and Landscape Capacity Study (December 2011)

- Market Harborough Landscape Character Assessment (April 2009)

- Rural Centres Landscape Character Assessment and Landscape Capacity Study (July 2014) and Houghton on the Hill Landscape Capcity Assessment (April 2016)

Further general information on landscape character assessments can be sourced from Natural England.

2. Does the site layout incorporate a clear green infrastructure?

10.13 Green infrastructure (G.I) is a network of green spaces and environmental features that link together within the surrounding landscape.

10.14 While isolated landscape features (such as parks, woodlands and allotments etc) can provide a range of benefits, where they are strategically connected to other nearby features, these benefits to the environment and the local community are significantly increased.

10.15 Not only should early consideration be given to linking useable green spaces within the development, but also to how these green spaces link to any wider G.I in the surrounding area. A G.I network should not simply stop at the site boundaries but create opportunities to link into the surrounding area.

3. Are existing site features protected and enhanced within the proposed layout of the development?

10.16 The value of retained natural features is significant, and existing features such as wooded areas, trees, hedgerows and watercourses can contribute to the character of a new development and create a sense of early maturity. Where practical, existing features should be retained and incorporated into the layout of the site. The following should be considered:

- Does the existing topography of the site provide interesting viewpoints? Consider how these could be incorporated into the site layout.

- Does the site contain wooded areas, mature trees and hedgerows? These can add significant value to the character of a development site and the design should seek to plant new trees where possible.

- Does the site have existing ecological value or certain habitats which need to be protected and enhanced as part of the development?

- Can existing watercourses be utilised as part of the landscape design? Where appropriately incorporated, these can add significant interest to open space areas.

- If a neighbouring site contains existing natural features, consider how these can be linked to new "green features" in the proposed development.

4. Is the open space well designed and usable?

10.17 If there is a requirement for the provision of more formal green space within the site, such as play areas, parks and sports facilities, they should be of high quality design. Where these spaces are not appropriately designed, they can often be to the detriment of the surrounding area.

10.18 When designing a formal open space, the following should be considered:

- Does the area have a clear purpose and use? It is important to consider what type of open space is being designed and what its intended use will be. Areas that do not have a clear purpose or use are often underused. Areas marked as "open space" which do not have a clear purpose, use and design are not considered to be acceptable.

- Does the open space contribute to the character of the surrounding area? Understanding the existing character of the surrounding area is the first step in designing a green space that contributes to the distinctiveness and identity of the area. Regardless of the end use of the space, it should reflect and enhance the character of its surroundings, or where this is not possible, create a new character for the development.

- Is the open space multi functional and sustainable? All types of open space should have an element of multifunctionality and sustainability. Consider how a sports pitch might be used as part of a sustainable drainage system? Could the park be used for community events and celebrations? Are gardens designed to encourage wildlife and add to the biodiversity of the area?

- Does the area have a clear circulation? How people move within and access an open space is key to creating a successful design. Consideration should be given to how users might want access the open space initially and also how they would walk or cycle around it. Areas should have clear routes that enable access for all.

- Is play equipment is required? Areas of open space often are required to contain an element of play equipment for varying age groups. In these situations, the incorporation of "natural play" elements should be used where possible. Large play boulders, mounds and tunnels can add significant value to the appearance and enjoyment of play areas in open spaces.

5. Does the proposed street layout and design incorporate appropriate tree and shrub planting?

10.19 Some of the most effective landscaping associated with new development is achieved through appropriate road layouts and street design. This is often where the character of the development can be clearly emphasised and key routes through the site can be highlighted.

10.20 Street trees should be included as part of the landscape design for all developments. Not only can this type of planting help to enclose the roadway and give a feeling of quality, it can also help to create valuable shade areas in the summer months, improve air quality and increase the biodiversity value of the area.

10.21 The appropriate use of tree planting to create avenues and planted parking areas can help to give a sense of direction and place within a development, especially when used on the key routes.

10.22 The provision of individual front gardens (rather than just paving and hard surfacing) in the street not only contributes to the character and distinctiveness of an area, but also allows new residents to express their individuality and can significantly contribute to the habitat and wildlife potential of the site as a whole.

6. Do the planting and street furniture details reflect the overall design?

10.23 Even where the overall design of the green spaces and networks for a site is well considered and designed, its quality can be significantly reduced by not selecting appropriate planting, furniture and surfacing etc. To ensure that the overall design is not diminished, the following should be considered:

- The planting choice through the site should clearly reinforce the overall design of the green spaces. Trees and plants should be selected that are appropriate for their intended surroundings, and, where appropriate, native species (of local provenance) should be chosen.

- Interest can be added to a scheme by using surfacing and materials in an imaginative way. Consider how furniture choices could impact on the use of a space, is formal seating needed? Could shaped boulders be utilised? Could standard bollards and railings be replaced by more creative structures?

MAINTENANCE OF LANDSCAPE

10.24 The success of new landscape features and green spaces not only depends on high quality design, but also appropriate and continued management. Regardless of the quality of a particular design for newly landscaped areas, if inadequate provision has been made for ongoing maintenance they can become unattractive and underused. The most common causes of failure in landscaping and planting schemes include:

- Poor ground preparation - Trees and shrubs planted into compacted and nutrient poor soil are unlikely to thrive and may die.

- Soil contamination and weed growth - Contaminants within the soil and heavy weed growth can have a significant affect on newly planted areas, preventing establishment and inhibiting growth.

- Competition for water and nutrients - New planting can become over dominated by existing grasses and shrubs, even well kept grasses around new trees will reduce the growth rate of new trees.

- Animal damage - Unless new planting is protected, animal damage can result in huge planting losses. Methods of protection should be appropriate to the surrounding area, for example, where deer are known to be present the protection level will be significantly increased.

- Mechanical damage - Trees which are unprotected by guards around the base of the trunk can be easily damaged by strimming and mowing.

- Poor aftercare - All elements of newly planted landscapes can fail if appropriate aftercare is not received.

10.25 Where developments require the provision of new landscaping, a maintenance plan should be submitted with the planting details, providing site specific details for each new planted area. The period of time to which any maintenance plan applies will depend on the site conditions and proposed planting, and will be set via the associated planning conditions for the development. Applicants are advised that planning conditions generally require replacement planting where plants have failed to become established within the first five years. Maintenance details should be submitted with all landscaping schemes.

10.26 To ensure that all new landscapes are appropriately managed from the outset, identification of who will manage each area should be established during the planning process.

TREES/HEDGEROWS AND DEVELOPMENT

10.27 Trees and woodlands are considered to be some of the most visually significant landscape features that define the character of our towns and villages. Trees are a key part of our distinctive area.

10.28 Existing trees can significantly contribute to the setting of new developments, and can give the impression of early maturity and increased design quality by creating intrinsic character. Because of their importance, local planning authorities in the UK have a duty to consider tree protection and planting when assessing planning applications for development.

10.29 Without appropriate consideration, existing trees and hedges can be easily damaged and lost through development. Damage can occur to trees through thoughtless construction practices such as vehicle collisions and root severance, as well as through more indirect factors, such as changes in the surrounding ground levels, compaction of the soil structure and contamination. One movement of a heavy vehicle over a tree's roots is enough to cause irreparable damage, while trenching and compaction causes excessive damage to trees all too frequently.

A Guide to BS5387:2012

10.30 British Standard 5837:2012 (BS 5837:2012 - Trees in relation to design, demolition and construction - Recommendations) provides clear guidance on how trees and hedges should be accounted for as part of developments to ensure appropriate retention, protection and management. It is the key document used by the Council when assessing planning applications where trees and hedges are a material consideration and its requirements should be closely followed by applicants.

10.31 Where trees and hedges are a consideration, a number of tree specific reports and surveys will be required at various stages of the planning process. These cover all stages of a development from the initial site and tree survey, through the construction of new buildings, to future planting and landscape maintenance.

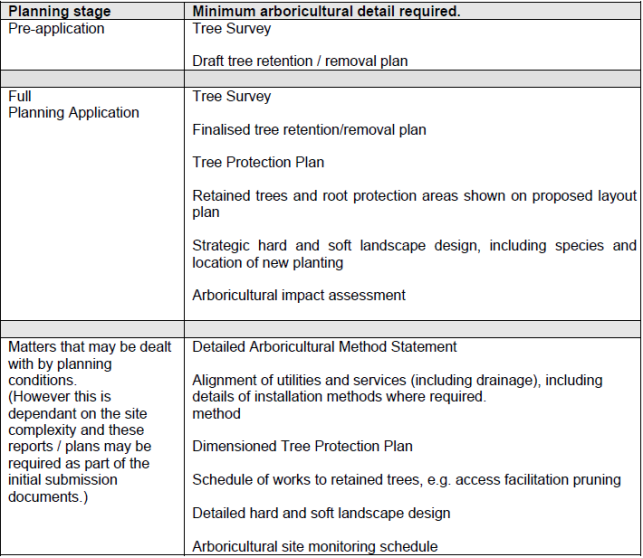

10.32 Fig. 10.1 outlines the tree based information that may be required at each stage of the planning process, depending on the size of the site, tree cover and overall complexity. Further clarification can be sought from the Council regarding the level of detail required for a particular application prior to submission. The remainder of this chapter provides a brief description of each of the reports and plans listed below. (Fig. 10.1)

Fig. 10.1 Information requirements summary

Tree survey

10.33 The starting point in producing a successful design is the gathering of good baseline information. A tree survey should be undertaken as part of the initial site investigations, and should record all relevant information for trees on and adjacent to the site. This may include details of habitats and protected species contained within the trees where appropriate.

10.34 As a result of a Tree Survey, the existing trees will fall within one of four categories (A, B, C or U) depending on their quality. Those in category A are considered to be the most desirable to retain, with those which are clearly dead being recorded as U. BS5837: 2012 provides clear guidance on the use of these retention categories.

10.35 The baseline data collected in the survey should be made available to all relevant parties in the planning process at an early stage as it forms an important part of the evidence base underpinning the Design and Access Statement. The classification of the trees should be based on the condition and value of the trees at the time of the study, and not a preconceived layout for the site, and may also include (where relevant) details of any nearby veteran and/or ancient trees.

Tree Retention plan

10.36 A plan showing trees proposed for retention and removal should be submitted in draft during any pre application discussions with the Council, or as a finalised version when submitting a planning application. It should be to a recognisable scale and record all onsite trees. It should show the following:

- Trees to be retained: marked with their survey numbers and circled with a continuous line.

- Trees to be removed: marked with their survey numbers and circled with a dashed line or similar.

Tree Protection Plan

10.37 A Tree Protection Plan shows how the retained trees and hedges will be physically protected during site clearance and construction of the development. It should be superimposed over a final site layout drawing and clearly indicate the precise location of all protective barriers and proposed hard surfacing.

10.38 The location of protective barriers around retained trees should be based on the required Root Protection Areas (RPAs) rather than an area which fits comfortably around the construction. BS 5837:2012 sets out a specific method for the calculation of RPA's, however this can be simply translated for single stemmed trees, by multiplying the diameter the trunk of each tree by 12.

10.39 Any required ground protection or commentary on alternative protection should also be noted on the Tree Protection Plan. Areas designated by the protective fencing as construction exclusion zones (CEZ's) should not be altered or disturbed without the prior agreement of the Local Planning Authority.

10.40 RPZs should be denoted on site by the use of securing "herras" style fencing which is clearly signed as a "Construction exclusion zone". The use of chestnut paling or plastic mesh is not appropriate. The protective fencing should be erected prior to any onsite works and remain in place until the completion of the development. Where full Root Protection Areas are not possible due to the constraints of the site, alternative methods of ground protection should be used.

Arboricultural Impact Assessment

10.41 An Arboricultural Impact Assessment (AIA) should draw on all of the baseline tree information and the proposed site layout, and provide an evaluation of the direct and indirect impacts of the development on the nearby trees.

10.42 It should take account of any required tree loss to facilitate the layout, discuss the elements of the proposals that could have a damaging arboricultural impact and propose, where appropriate, mitigation measures. An AIA should include copies of the Tree Survey, the Tree Retention / Removal Plan and provide details of any required facilitation pruning.

Arboricultural Method Statement

10.43 The Council may also ask for the submission and approval of an Arboricultural Method Statement. These statements detail how the development will actually take place around any retained trees.

10.44 While the level of detail required in a Aboricultural Method Statement will vary from site to site, they generally cover the same basic topics such as how demolition will occur, where any materials will be stored and how the development will be phased. The Council can advise applicants on the content of the method statement, should this be required.

Designing with trees

10.45 While it is recognised that many factors will need to be taken into consideration when designing the layout of a new development, tree retention has the potential to significantly contribute to the site's character and needs to be accounted for at an early stage.

10.46 Following the completion of the surveys and analysis of the site described in paragraphs above; consideration should be given to which trees are the most suitable for retention. Trees of the highest quality (those categorised as A and B trees in the Tree Survey) should be retained as part of the proposed layout, as they are likely to have the most positive contribution to their surroundings.

10.47 Trees of moderate and low value (category C and below) should not automatically be considered for removal, as they may play a useful role in site screening, or as an important habitat feature. As part of the design the following factors should be considered:

- Physical dimensions of retained trees

The physical size and shape of the trees is likely to be the first factor to be considered. The crown shape and spread, along with the root area should be considered as part of the design.

- Current and future relationships

A realistic assessment of the current and future relationships between the existing trees and new structures should be made. Retained trees that are inappropriately incorporated into site layout can become a nuisance, often leading to pressure for them to be removed. Larger trees might be better suited to areas of open space or more extensive private gardens where conflict is less likely to occur. The potential impact of the shading caused by tree canopies should be considered, and situations where dense shading could be problem should be avoided. Seasonal problems such as Honeydew and leaf drop might also need to be considered.

- Roadways and surfacing

Access into a site is often one of the first issues to be considered when a development is planned, and can have a significant impact on existing trees. Traditional road construction and surfacing does not allow water and nutrients to percolate through to the soil (and roots) beneath. Also the excavation and compaction required to construct an access can easily damage the soil structure and the root areas of retained trees. To avoid this type of damage, main access driveways and other hard surfaces should fully avoid the RPA's of retained trees. Where this is not possible, the use of alternative, porous road, "no dig" construction techniques should be used.

- Alternative construction techniques

On particularly constrained sites, the use of alternative foundations may be required. These should be discussed with the Council during the planning process.

- Services

Requirements for above and below ground services should be considered. Underground services should not cut through the required root protection areas for retained trees. Where there is no alternative route, specialist installation methods should be considered.

Construction and aftercare

10.48 In addition to the design and layout of a development, the physical practicalities of developing the site should be considered as part of the Arboricultural Method Statement. Significant time may have been taken to formulate an appropriate site layout, taking full account of any onsite trees, and yet they can be easily and significantly damaged at all stages of the construction.

10.49 While the Arboricultural Method Statement may include details of construction phasing, protection and pruning that may be required to allow the development to take place, this information is often not passed on to site clearance and construction contractors.

10.50 To ensure that all parties are aware of the arboricultural factors of the development and understand the importance of the construction exclusion zones, full details of protected areas and works likely to affect the trees should be made available. All protected areas should be appropriately signed, and regular meetings held at key stages of the development with the appointed Arboricultural Consultant. In some cases, the Council may wish to monitor the progress of the site, especially where trees may be particularly sensitive or the site is very constrained.